By Olivia Heffernan, a master’s candidate at Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs

On November 14, the Weatherhead East Asian Institute at Columbia University hosted a lecture titled “Understanding the Rohingya Crisis.” Panelists addressed the historical roots of ongoing violent conflict in Myanmar, including the “othering” of the minority Rohingya Muslims and escalating fear of Islam, as well as the responsibility of the international community to respond to the country’s human rights crisis. The lack of response raises questions about the international community’s commitment to protecting peace and precipitates another interesting discussion: What does an ethnic cleansing overseen by a Nobel Peace Prize winner mean for the credibility of the award itself?

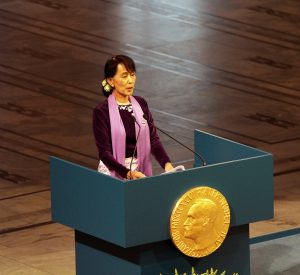

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s de facto leader and first state counselor, was conferred the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for her admirable fight for democracy in Myanmar during 15 years under house arrest as a political prisoner. However, actions speak louder than words. Aung San Suu Kyi’s complicity to the killings and expulsions of Rohingya Muslims raises questions about her promise to ensure peace and democracy in Myanmar.

Panelists of the event provided context for the current crisis and cited startling statistics of pervasive and systematic violence against the Rohingya, violence that constitutes ethnic cleansing by U.N. standards. Human Rights Watch reports that military repression has resulted in the deaths of thousands of Rohingya Muslims, forcing at least 600,000 people to flee their homes since 2016. The U.N. continues to deliberate on whether the killings constitute a genocide. Furthermore, panelist Mayesha Alam mentioned that no state besides Indonesia criticized the government of Myanmar for its inhumane treatment of the Rohingya during the recent ASEAN summit. The lack of international response delegitimizes international covenants such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and principles such as the Responsibility to Protect.

In an open letter to Aung San Suu Kyi, fellow Nobel Peace Prize winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu wrote, “My dear sister: if the political price of your ascension to the highest office in Myanmar is your silence, the price is surely too steep.” Malala Yousafzai, another Nobel Peace Laureate, also expressed her disappointment in a statement on Twitter: “Over the last several years, I have repeatedly condemned this tragic and shameful treatment. I am still waiting for my fellow Nobel laureate Aung San Suu Kyi to do the same. The world is waiting and the Rohingya Muslims are waiting.” Similarly, Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch and long time supporter of Aung San Suu Kyi, has said, “Now that she’s in power, she symbolizes cowardly complicity in the deadly tyranny being visited on the Rohingya.”

In her first public address since the violent military crackdown on the Rakhine state, Aung San Suu Kyi’s statements contradicted her actions. She displaced blame and denied culpability, claiming that the Myanmar government “condemns all human rights violations and unlawful violence.” She also made false claims, assuring the audience that Rohingya Muslims did not face discrimination and had equal access to healthcare and education— a blatant lie according to international human rights advocates. Perhaps more concerning, in the same speech, Aung San Suu Kyi announced that despite widespread condemnation, she does not fear international scrutiny.

Despite ubiquitous disappointment in Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership and calls for the revocation of her award, former Nobel Prize committee member Gunnar Stalsett defended the committee’s choice: “The principle we follow in the decision is not a declaration of a saint…when the decision has been made and the award has been given, that ends the responsibility of the committee.”

However, Stalsett’s above statement is dangerous— it insinuates that the Nobel Peace Prize committee has no interest in the actions of their awardees post-conferment. Not condemning Aung San Suu Kyi for her direct contradiction of the award’s values discredits the legitimacy of the prize. Recipients of the Nobel Peace Prize should be held to higher standards and accountable for their actions. At the least, they should face repercussions for committing injustices. While a Nobel Peace Prize has never been revoked, in this case, rescinding the award appears to be one of the more obvious and symbolic means of sending an important message to Aung San Suu Kyi: reputation and power do not acquit anyone of wrongdoing in the face of human rights violations.

Olivia Heffernan is a student at Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs concentrating in social and urban policy and specializing in journalism. She is president of the Criminal Justice Reform Working Group (CJR) and has previously worked for human rights-related nonprofits. Olivia is originally from Washington, D.C., but she has spent multiple years living abroad.

The post is interesting. Can I share it?